These days, not a month goes by that we hear about a new major ransomware attack. Initially, the ransom demands were in the few hundred dollars, but those have now escalated in the millions. So how did we get to the point where our data and services could be held for ransom? And with a single attack paying out millions of dollars, should we be hopeful for this trend to ever end?

Dr. Joseph L. Popp, among his many other achievements in the field of biology, is attributed with the first use of computer software to demand a ransom. Popp dispatched 20,000 floppy disks, labelled "AIDS Information - Introductory Diskette," to hundreds of medical research institutes across 90 countries in December 1989 using the postal service. Each disk included an interactive survey that measured a person's risk of contracting AIDS based on the responses. Alongside the survey, the first ransomware - the "AIDS Trojan" encrypted files on user's computers after rebooting a set number of times.

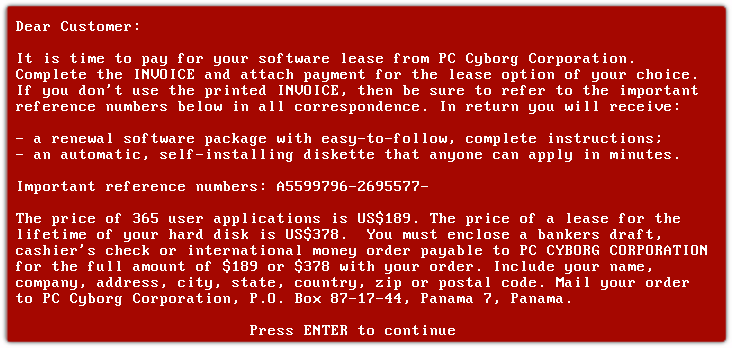

Printers connected to the infected computers printed instructions to send a banker's draft, cashier's check, or international money order for $189 to a post office box in Panama. He planned to distribute an additional 2 million "AIDS" disks before being arrested on his way back to the US from a World Health Organization AIDS seminar. Despite the evidence against Dr. Popp, he was never convicted for the crime.

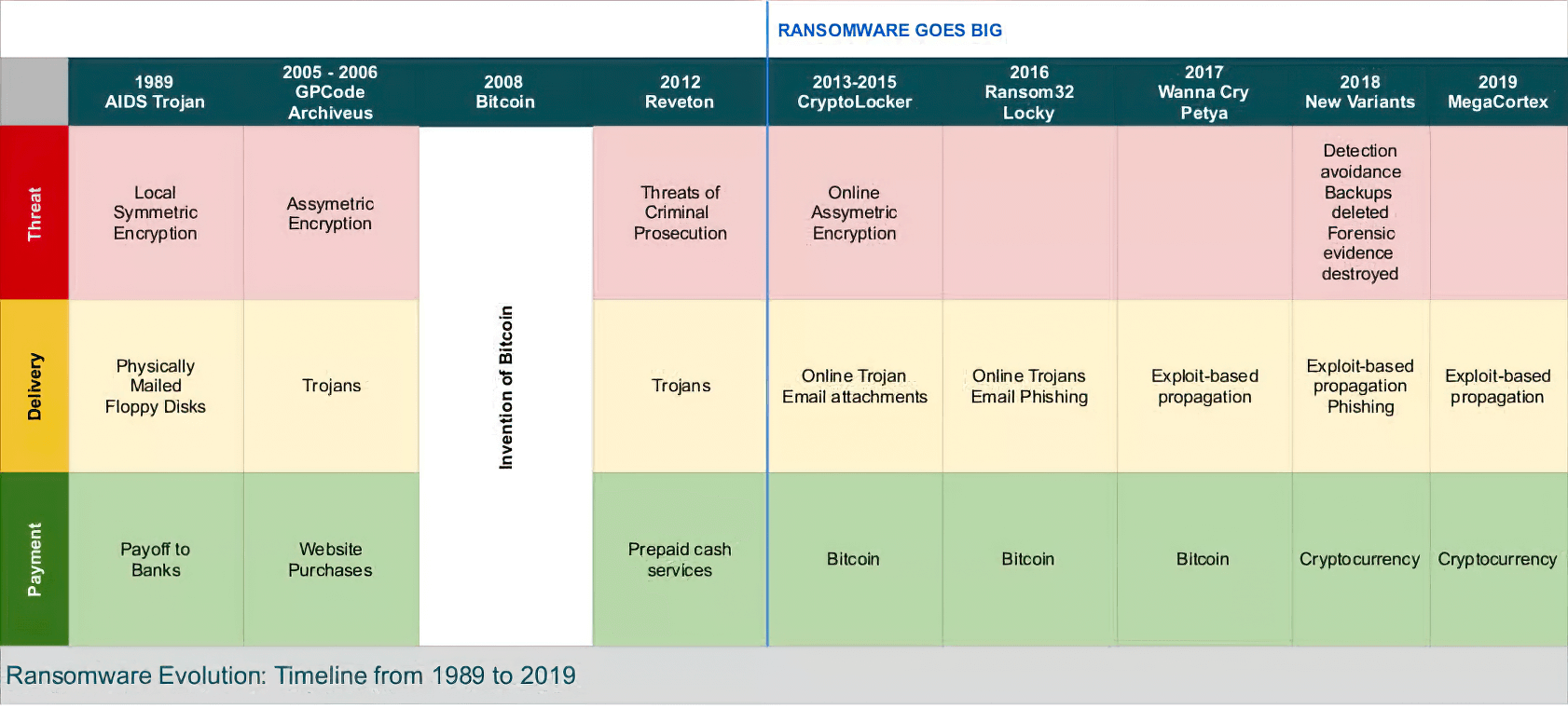

Fortunately for computer experts at the time, Dr. Popp's code used symmetric encryption and a decryption tool was created to mitigate the first-ever ransomware. With no significant ransomware attacks appearing between 1991 and 2004, could the computer world rest easy? Some would say that this was the calm before the storm.

By the early 2000s, cybercriminals had a ransomware blueprint and access to three essential bits of technology that Dr. Popp did not...

(1) An efficient and super fast delivery system that connects millions of computers worldwide, i.e. the world wide web. (2) Access to more robust asymmetric cryptography tools to encrypt impossible to crack files. (3) A payment platform that provides speed, anonymity, and the capability of automating decryption tasks upon payment, like Bitcoin.

Put together these elements and that's when ransomware really took off. What follows is a brief summary of a key events in ransomware's history:

In addition to using advances in technology to their advantage, ransomware attackers are more aggressive and using creative methods to improve the success of ransom payouts, though thankfully that success rate is finally on the decline.

Cybercriminals have been shifting their focus to critical infrastructure and larger organizations. For example, in 2016, several hospitals were hit by ransomware, including Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center, Ottawa Hospital, and Kentucky Methodist Hospital, to name a few. In all cases, hospital devices were locked or medical files encrypted, putting patient lives in danger.

Some hospitals were fortunate and had in place rigorous backup and recovery policies. But, unfortunately, others needed to pay the ransom to restore health services as quickly as possible.

(click to enlarge)

In March 2018, many online services for the City of Atlanta were taken offline after a ransomware attack. The ransom of $55,000 in Bitcoin was not paid, but early projection put recovery costs around $2.6 million.

In May 2021, the DarkSide ransomware took down critical infrastructure responsible for delivering 45% of the gasoline consumed across 13 US states for one week. The victim of this particular attack, Colonial Pipeline, paid $4.4 million to regain their systems. Massive payouts like these only continue to drive attackers to find even more creative ways to cash out using ransomware.

Another tactic used is called 'Encrypt and Exfiltrate.' Attackers realized that the same network weaknesses that aided ransomware infection could be used to exfiltrate data. Aside from encrypting victim files, attackers steal sensitive data and threaten to publish the data if the ransom is not paid. Thus, even if an organization could recover from a ransomware attack using backups, it cannot afford a public data breach.

Vastaamo, a Finnish psychotherapy clinic with 40,000 patients, was the victim of a newer tactic called 'Triple Extortion.' As is the norm, medical files are encrypted, and a hefty ransom is demanded. However, the attackers also stole patient data. Shortly after the initial attack, patients received individual emails requesting smaller ransom amounts to avoid public disclosure of personal therapy session notes. Due to the data breach and financial damage, Vastaamo declared bankruptcy and ceased operations.

Large-capacity NAS drives from individuals has proven to be an attractive target in recent years, too, as QNAP and Asustor customers have unfortunately discovered. Deadbolt ransomware struck Asustor's internet-connected products in early 2022 and has hit QNAP's drives in multiple waves over the past couple of years.

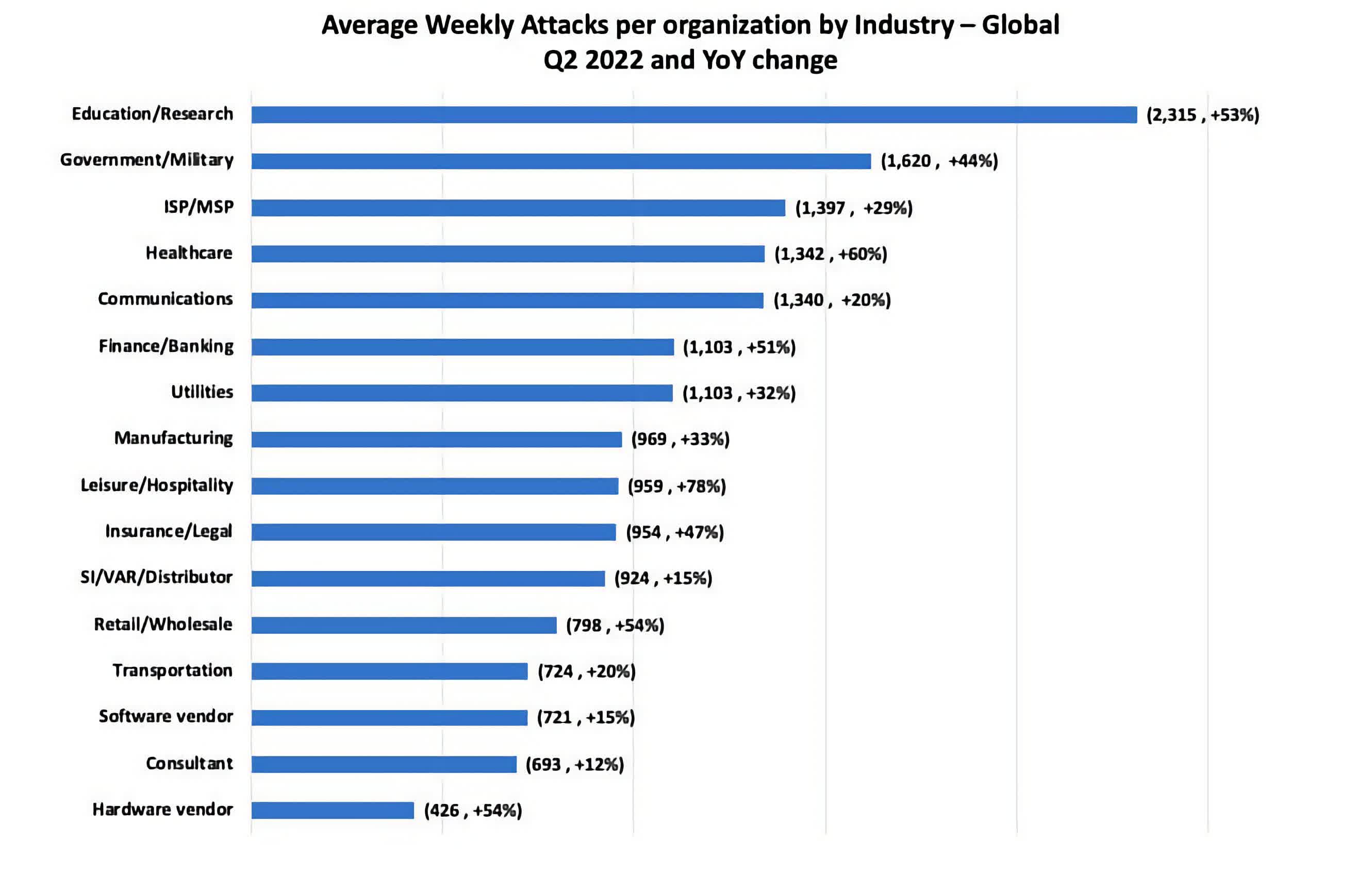

Cybersecurity Ventures reported ransom attacks were up 57% since the beginning of 2021 and cost businesses an estimated $20 billion in 2020, 75% higher than 2019. Ransomware attacks are also becoming very specific with victim selection, targeting organizations within industries like healthcare, utilities, and insurance/legal that offer critical services because they are more likely to pay a sizable ransom.

Ransomware attacks per organization per week by industry

Q2 2022 data via Check Point Research

The Education and Research sector continue to be the most heavily attacked industry, seeing a 53% increase year-over-year (2021-2022), followed by Government/Military, Internet Service Providers and Healthcare institutions.

About 40% of all new ransomware variants include data infiltration components to take advantage of double and triple-extortion techniques. In addition, REvil, a RaaS group, offers Distributed-Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks and voice-scrambled VoIP calls as a free service to its affiliates (the actual attackers that break into a system) to further pressure victims to pay the ransom within the designated time frame.

Why the sudden increase in ransomware attacks over the last decade? It is lucrative! Even if a small percentage of ransomware attacks succeed, they still yield a significant return on investment. Take, for example, the largest public ransom payouts to date:

Yet, these attacks only account for a tiny number of successful ransomware campaigns. Unfortunately, these same high profile payouts motivate attackers to keep looking for new ways to infect, spread and extort.

Another factor to consider: an ever-widening attack surface. In 2017, 55 traffic cameras were hit in Victoria, Australia by WannaCry due to human error. While the attack's impact was minimal, it does provide a hint of the devices that cyber criminals will target. Given the slow security update process and the increasing number of vulnerable Internet of Things (IoT) devices across the globe, this will inevitably open opportunities to ransomware operators.

Experts also fear that ransomware will start appearing in cloud services, mainly targeting Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) and Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS). Factor in new entrants, a new generation of youngsters inspired by TV shows like Mr. Robot. They have access to more resources like "Hack the Box" than any generation before them. These new entrants are eager to learn and even more eager to test out their skills.

Ransomware is at the center of a sophisticated and booming underground economy with all the markings of legitimate commerce. Imagine a community of highly skilled and collaborative malware developers, RaaS providers, ranked affiliates, IT and customer support teams, and even operators responsible for the attacker group's press releases and 'branding.'

As we give up personal data to various service providers and rely on technology for our everyday tasks and routines, we're unintentionally empowering ransomware attackers to kidnap and hold us hostage. Thus, we can only expect ransomware attacks to increase, become more aggressive and creative in ensuring ransom payments – possibly requesting the first payment to decrypt data and a second separate payment not to publish.

In early 2023, security firm Bitdefender released a tool to help MegaCortex ransomware victims unlock their files, which is great news for those that have had files locked down for years.

The tool is also available from No More Ransom. The site plays host to unlocking tools for more than 170 pieces of ransomware and variants including well-known examples like REvil and Ragnarok.

Ransomware victims have realized that even if they pay the ransom, there's no guarantee they will get their data back or that the ransomware actor will delete the "stolen" files without selling them to third parties on the dark web. The public perception of the ransomware phenomenon has matured as well, so data leaks don't carry the same risks for brand reputation of the last few years.

The Colonial Pipeline hack highlighted the vulnerability of modern society. The attack led to anxiety spreading across affected cities, which led to panic buying fuel, fuel shortages, and rising fuel prices.

Ransomware costs are not limited to ransom payouts. Damage and destruction of data, downtime, reduced productivity post-attack, expenses related to forensic investigation, system restoration, improving system security, and employee training are hidden and unplanned costs that follow an attack.

Law enforcement agencies are also concerned about the possibility that a cyberattack on hospitals will cause deaths. The negative impact on human lives and society by ransomware cannot be denied and no longer ignored.

Towards the end of 2020, the Ransomware Task Force (RTF) was launched. A coalition of over 60 members from various sectors – industry, government, law enforcement and countries – is dedicated to finding solutions to stop ransomware attacks. In April 2021, the RTF released the "Combating Ransomware: A Comprehensive Framework for Action" report detailing 48 priority recommendations to address ransomware.

The concerted effort is paying off.

While no arrests have been made, the FBI managed to recover 63.7 Bitcoin (~$2.3 million) of the ransom paid out in the Colonial Pipeline attack. The FBI and other law enforcement agencies worldwide were able to disrupt the NetWalker ransomware-as-a-service element used to communicate with victims. In 2021, the Emotet botnet was also taken down, an essential tool for delivering ransomware to victims via phishing.

In October 2021 authorities arrested a dozen individuals linked to more than 1,800 ransomware attacks across 71 countries. Police spent months combing through data collected during the arrests and the keys discovered by law enforcement led to the development of new unlocking tools for the MegaCortex ransomware as mentioned before.

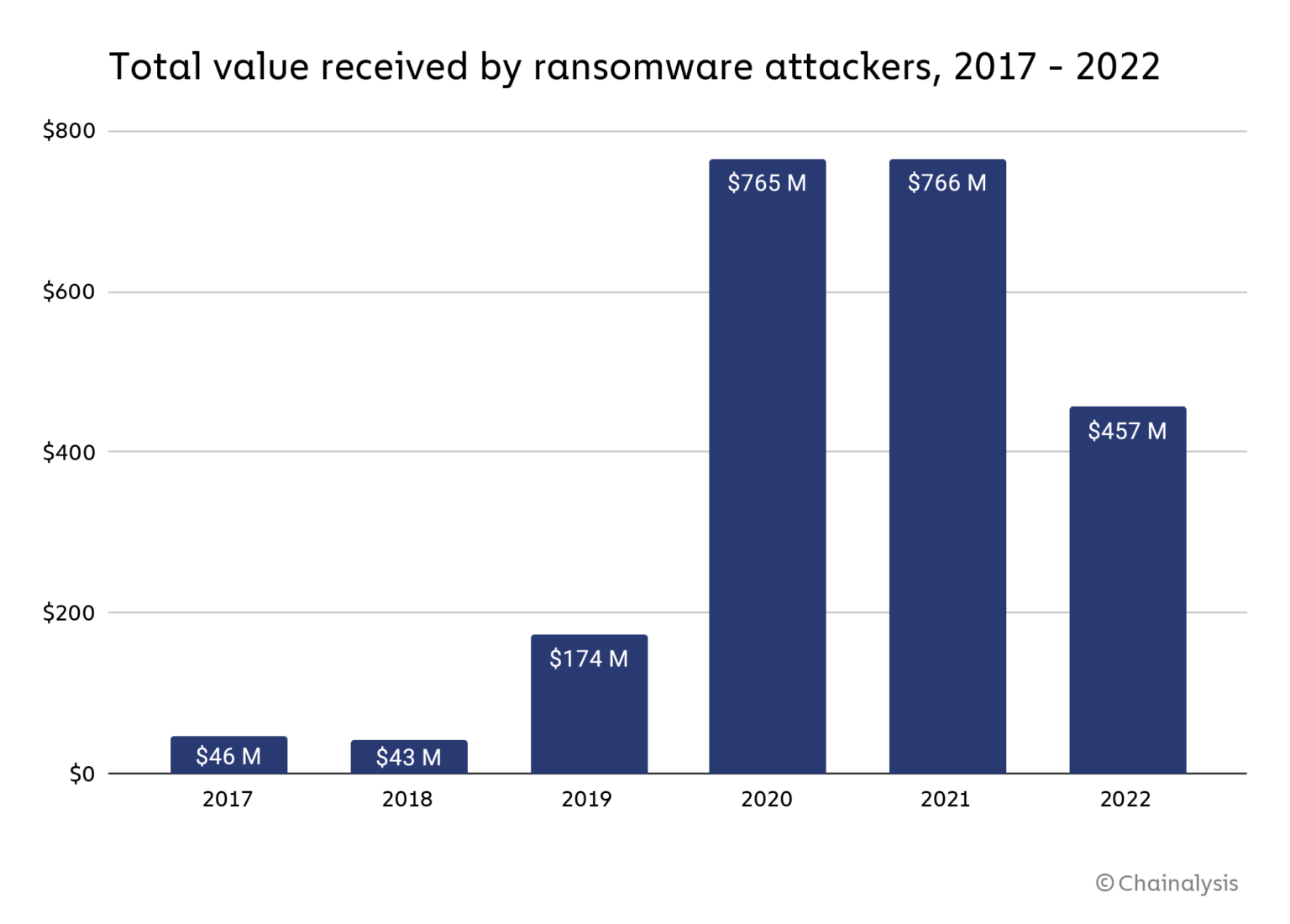

According to data provided by firm Chainalysis, ransomware revenues for 2022 have shrunk from $765.6 million to at least $456.8 million, or a -40.3% drop year-over-year. The volume of attacks is as impressive as ever, but the number of victims that refuse to pay the ransom has grown as well. Chainalysis has seen a sharp reduction in the number of ransomware victims willing to pay: they were 76% in 2019 but just 41% in 2022.

These may seem like a drop in the ocean compared to the number of ransomware attacks in the recent past, however public awareness and global organizations, government and private, are acknowledging and actively working to neutralize the ransomware threat, which are much necessary steps in the right direction.

Copyright © Powered by | The Evolution of Ransomware-春宵一刻网 | sitemap